VALE David Seargent

This is a member only article

Following is a copy of our founder, David Sergeant’s Eulogy.

Slide images are shown at the end.

[Slide 1]

[John] Dad lived a long life, and we want to spend quite a bit of time telling you about it. And remember, while it is sad that Dad is not with us anymore, we intend today to be a celebration of what was, unarguably, a remarkable life.

Some thanks before we start though: Isobel for presiding, Sydney Presbytery for allowing us to use this consecrated space, Genevieve, and Jyah for setting up the hall, Louisa, Alex and Neil for handling the technology, Peter for reading, Liz for accompanying our only hymn, and all of you for coming to remember Dad with us and to celebrate his life.

[Beth] David’s father was John Owen Sergeant (known as Jack), an Englishman from a Liberal Lincolnshire family, who had emigrated to Sydney to work at the North Head Quarantine Station early last century. He was a microbiologist, a skill that was needed to keep Sydney safe from infectious disease. On arriving in Australia, he wrote to his mother saying, “I have found a place called Manly, I doubt that you will ever see me again.” True to his word, he lived in Manly until his death in 1947.

David’s mother was Helen Joyce Chinnick. She was from a Cornish family and was born in the hamlet of Burraga in Central Western NSW … in what we would now call Wiradjuri country. Helen was a nurse. If she had been born today, she probably would have trained as a doctor. Aged 25, she married Jack, who was by then 50.

David was born in the spring of 1933, at home, in Ocean Road Manly, on the cliff overlooking Manly Oval. He was an only child.

Later in his life, David wanted to ensure that his own family would have at least two children, and, later still, he pronounced himself very happy that both of his sons had married into very large, warm and loving families, thereby gaining a full complement of brothers and sisters-in-law. Both the Powells and the Crawfords are represented here today.

Dad’s father Jack, once he judged that his son was old enough to be capable of intellectual discourse (babies and infants were women’s business), inculcated in his son an appreciation of the scientific method, just as our father subsequently did for us. Perhaps because of his father’s influence, Dad’s religion, through most of his life, was truth … and his pathway to truth was reason.

We simply don’t know whether or how his beliefs changed as his faculties faded and his life drew to its close, but we do know that he greatly appreciated the frequent visits of the Chaplain at the Marion. The fact remains, though, that Dad lived a Christian life, as judged by his actions and his compassion for those in need, while always being sceptical about Christianity itself.

[Chris] As well as a love of science, Dad’s father also fostered an interesting in gardening that, similarly, was to prove lifelong.

His mother Helen raised Dad to appreciate serious music, classical music. She was the secretary of the Manly Music Society and ensured that there was complete silence in the house whenever her wireless was playing real music. There was no popular music. That was for other people.

The three pieces that have been playing as you arrived, and which will play at the end of the service, were some of Dad’s favourites. They are listed on the order of service. [Finlandia Op.26, No.7 (Sibelius), Adagio of Spartacus & Phrygia No.2,1 (Khachaturian), Violin Concerto in D Major (Beethoven)]

[John] Dad attended Mosman Prep. School for his primary education, after which he was enrolled at Barker College in Hornsby. That is not an easy commute from Balgowlah today, let alone then.

On weekends, during his boyhood, Dad sailed Manly Juniors at the Spit. He also enjoyed tennis (but always complained of having hot feet). This was a recurring theme. In summer, Dad would make his bed with the top sheet folded back, just like a normal person, but he would also fold back the base so that his feet kept cool overnight.

Jack Sergeant died when Dad was aged 14. There is never a good time to lose one’s father, but this was an awful time.

His poor mother was now a widow with a no doubt demanding teenager. She thought that it would be best if Dad could board at Barker College. This must have been a very hard decision for them both. At Barker, under the long-serving headmaster Dr Leslie, Dad was a good student but certainly not a happy one. No doubt he missed both his parents.

It being wartime, boarding house food (is that an oxymoron) contained a very high proportion of the root vegetable known as swede. Dad swore never to eat swede again, although he did rather fancy parsnip, as we will see later.

Still, he made a number of friends at Barker, whom his mother delighted in inviting home for dinner from time to time. She was an excellent cook.

Dad detested Barker as an institution. Despite this, when he left the School, in 1950, his mother paid the necessary fees to make him a life member of the Old Barkers’ Union, an organisation with the unhappy knack of tracking his address through various house moves over the years – Its quarterly newsletter invariably went straight into the waste paper bin unopened. One day, I fished it out, out of curiosity. I said, “Hey Dad, it says that the boarding house burnt down over the holidays.” “Give me that!” he said eagerly.

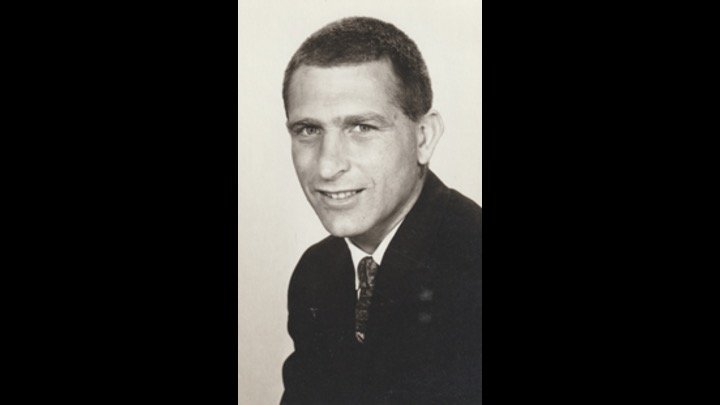

[Chris] After school, Dad travelled to Europe with his mother and met his numerous English Sergeant relatives. Here is his first passport photo. [Slide 2] He then enrolled in a Bachelor of Science in Agriculture at the University of Sydney in 1951. Our parents did not meet at university. Mum had finished in 1949, graduating in 1950.

While at university, David jackerooed over summer with the Tourle family at The Springs, south of Dubbo, in the Toongi district. This is also Wiradjuri country. The Tourles are still there, although they live in a more modern house on the property now. This is the old homestead, where Dad stayed with the Tourles. [Slide 3]

While at Sydney Uni, Dad finally had the enjoyable educational experience that he had lacked at school, with the traditional four years of an Ag degree crammed into six. He was one of the cool students, was involved in the Students Representative Council and would travel to university from Balgowlah on a Matchless motorbike.

During this time, he had a crash on the Sydney Harbour Bridge on a rainy night and lost consciousness. Apparently, he came to, assessed the situation, and then limped home pushing his damaged motorbike all the way to Balgowlah. Did we mention that he was strong willed?

Dad finished off his degree in 1956 and here is his final year class, with Dad front and centre, as the Faculty’s SRC representative. [Slide 4]

[John] After a brief trip to Lae and Mt Hagen in New Guinea, Dad started work at the CSIRO, as a researcher in microbial genetics. [Slide 5] He was very fond of this photo. Many years later, even after Alzheimer’s had started to eat away at his sense of identity, Dad was thrilled to be given a private tour of my daughter Genevieve’s chemistry laboratory at Sydney Uni, donning a lab coat and safety glasses and marvelling at the state-of-the-art facilities. He always felt at home in a science lab, and this was a highlight of his later years. But back to our narrative.

Dad met a young woman named Beth Manson at Cooma Railway Station one winter evening. Dad, in his overcoat, looked properly dressed for the climate and was assumed by Mum to be either a local or, more likely, a railway official of some sort. She asked him for directions to the Youth Hostel where, as it turned out, they both intended to stay as they tried out skiing. There was not much snow at Kiandra that year, so they went to Yarrangobilly Caves instead.

David and Beth were married on the 11th of February 1961, at St Andrew’s Church of England Roseville. Here are some photos of the happy day. [Slide 6, Slide 7]

On their honeymoon, the newlyweds had a very bad car crash near Gundagai, rolling the car several times. Both had broken bones, although Dad was the more seriously injured of the two, with broken ribs and collarbone on both sides and head trauma resulting, again, in a loss of consciousness, this time prolonged. When he eventually woke up in hospital, he was unaware of his name, unable to recognise his new wife, unsure of the name of the prime minister (it was Menzies, by the way). However, he did say “I think that I’m a scientist.”

Earlier this month, we had to provide his occupation, to be shown on his death certificate, so we chose “Scientist”. And he was very much a scientist – rational, logical, and practical.

He had tried his hand at teaching science at high school level, although after one week at Balgowlah Boys High School, he concluded that scientific research and teaching adults who actually wanted to learn might suit him better.

[Beth] When we first married, David was tired of being the man of the house, having been in this position since his father had died while he was still at school. So, we looked for a bit of adventure before settling down to start a family. Through Sydney University’s graduate employment service, we decided on a role in newly independent Nigeria. This was in 1961.

In Nigeria, David would be teaching basic science to primary school teachers, on an ecumenical campus at Asaba, on the Niger. Nigeria did not have an extensive high school system at that time, so it was important that primary school teachers had a good grounding in science. His Ag Science degree was ideal. The different tribal cultures intrigued us both. We were in Igbo country, although close to the Yoruba people, and there was a mixture of tribal backgrounds among the students.

Our first child, John, was born in 1964. I went to London for the birth, staying with one of David’s cousins, and then, in due course, returned with John to Asaba for a further two and a half years.

Then, in 1967, came civil war! Expat women and children were evacuated. The Igbo controlled the area where we lived, which they proclaimed as independent Biafra. They were in rebellion against the central government. Surprisingly, teaching practice for students continued, despite the war. Very few people realised how bad things would soon become.

David, with some other staff members, got permission from the local commander to set up part of the campus, on the outskirts of Asaba, as a place for the protection of a tribal minority whom the local majority Igbo disliked. Food was very scarce, but they somehow kept everyone alive.

However, a rebel lieutenant refused to accept this camp, ordering its unfortunate occupants to dig a mass grave. David’s group demanded to see higher authority and were taken into Asaba township. Arriving there, they were initially mistaken for captured mercenaries. David was hit on the head with a wooden rifle butt. He collapsed unconscious and was saved from summary execution only when the local archdeacon recognised him. He survived but was now a prisoner. The people he had been trying to protect were all killed.

Government forces were by this stage closing in and the Igbo soldiers retreated eastwards across the Niger deeper into Biafra, taking David and two other teachers with them. As Europeans, they presumably had some value in a horrific war where life was otherwise very cheap.

David was taken to a big hospital in Biafra, where he recovered from his injuries. Unable to leave, because Biafra was cut off from the rest of the world, he found useful work in a remote leprosy settlement. When the civil war fighting again came close, David met with the rebel troops defending the area and had the temerity to ask for safe passage across the lines, to the government side. This request was not well-received. The local Biafran commander, who was nicknamed “The Scorpion” held him overnight, either to be executed or released in the morning. David did not know which.

Thankfully, the next morning, he was let go and, in the confusion of war, somehow found his own way across the lines. His two fellow teachers also survived the war, although in different ways.

We later discovered that the British, while firmly on the side of the Nigerian Government, nevertheless maintained clandestine channels of communication with the Biafran rebels. Somehow, the British appear to have made representations to the Scorpion’s group to have David released. The Australian High Commission in Lagos issued him with a cobbled-together passport, using his 1951 passport photo and a cut-out signature from another document. This is the passport [Slide 8]. As you can see, it is a genuine forgery.

David returned to Sydney and, soon after he got back, we went to see the film Dr Zhivago. There is a scene in the film where the Lieutenant is struck down with a rifle butt. David and I leapt into each other’s arms.

As a bit of a postscript, the Government forces were often no better than the Biafrans. Tribal motivations were dominant. When the Government troops, who were mainly from the north of the country, recaptured Asaba, where we had been living, they conducted what proved to be the largest massacre of the war, slaughtering the local Igbo wholesale. The result was that, by the end of the conflict, both the minority tribe and the majority group had been successively massacred. Asaba as a township had to start again, more or less from scratch.

Today, all units of the Nigerian Army are multi-tribal and multi-religious as a matter of policy. They are frequently re-deployed to different parts of the country. The army, and the football team, have become the glue holding an ethnically diverse nation together. While there have been the usual inter-tribal tensions and simmering Christian-Muslim conflicts, outright war has been prevented for the last 50 years. Asaba is now a major city, and its stadium is the home ground of Nigeria’s men’s football team: the Super Eagles.

[John] After his return from Africa, we lived with his mother in Balgowlah and with his mother-in-law in Roseville before the family of three moved to a rented flat in Cammeray. Dad was considering returning to devastated Biafra at this time, to help with the reconstruction. He got as far as having a passport photo taken: the one on the cover of today’s order of service. However, Mum said “no’. She couldn’t face the prospect. Instead, in 1970, David and Beth bought a house at 48 Illilliwa Street in Cremorne. (Illilliwa means “go west” in Eora. This subliminal message proved to be prophetic).

While living at Cremorne, Dad worked at the Sydney office of the Commonwealth Department of Education. His particular area was the Colombo Plan: a program under which promising students from Southeast Asian nations were provided with scholarships to study at Australian universities. A number of these students became friends not just of Dad but of our family. It is very pleasing indeed that the son of one of those students is here with us today.

When the Colombo Plan ended, but still within the Commonwealth Education Department, Dad worked on aboriginal education, in which the Commonwealth now had an increased interest, following the passage of the 1967 referendum. This work suited him well and, again, it aligned with his values, which were always progressive and on the side of the marginalised and disadvantaged, both in Australia and overseas.

In 1970, Mum and Dad decided to adopt a baby boy. Actually, they had no choice of gender. Having only one children’s bedroom, they could only apply for a boy. Chris arrived in 1971.

[Chris] Quite recently, I was sent a copy of my original birth certificate. It felt quite strange to see all my details with another person’s name - very much what might be referred to as a sliding doors moment, which got me thinking about what my life would have been like as Adrian Peter Walsh.

I have been very fortunate in that the government agency that managed these things found a loving couple with a very pragmatic view on life and family. In some ways a not very typical family, but one that showed the way by deeds, if not always by words.

Having been fortunate enough to have met my birth mother - Jeannette, who is here today as well, I have come to realise that their views on life, social justice and particularly their commitment to support those who sometimes can’t help themselves, are very similar. It is as if Jeannette conspired with David and Beth to raise me in a certain way, although, of course, they didn’t even meet until much later.

Dad rarely passed judgement on us boys. So, when he expressed a view, one took note. I still remember the time that he took me aside and said that he was proud of the person I was becoming … which I interpreted as meaning that I was almost ready to be included in adult conversations and I was potentially becoming of interest…or something like that. I am sure that he got this from his own father.

And while today certainly has the capacity to be a sad occasion, I feel very fortunate to have been brought up in the way that I was - an appreciation that has only grown as I have had my own family, as we look to bring our children up with a Christian attitude to life, if not necessarily a structured approach to religion.

[John] So, by adopting Chris, Mum and Dad probably saved both of us from being only children. Chris wasn’t just added to our family. He changed it and, in a very real sense, he completed it. Adopting Chris turned out to be the best decision David and Beth ever made, in my opinion. [Slide 9] Here is a picture of our family in 1975, when Chris was 4 years old. The picture was taken by one of the Colombo Plan students.

At this time, Dad joined the North Sydney branch of the Labor Party. If ever there was a hopeless cause, it was that of the Labor Party on the Lower North Shore. We think that he’d be pleased to see a Teal independent holding North Sydney today … and equally pleased to see the former Liberal member for North Sydney’s daughter Allegra Spender representing Wentworth for the same progressive Teal cause.

As well as supporting the Labor Party, Dad also spent many weekend afternoons removing introduced weeds, like lantana, from the bushland around Sydney Harbour. He was not part of an organised bush care group. He just saw a need and did something about it himself.

Despite being on the affluent north shore, we lived very simply and cheaply, paying off the mortgage in six years and sending all available cash to fund development aid, having seen firsthand the devastation of war, poverty and starvation. At times, it seemed to Chris and me that there was a policy of enforced poverty and starvation at home; the only ice cream we ever tasted was homemade (it was actually pretty good, certainly very solid), dining out meant KFC, but no more than once per month. We learnt that blocks of chocolate were much cheaper than Easter eggs and would last for much longer, especially if only one square was consumed per day. Mum allowed herself a pittance for housekeeping and made do somehow.

There was no television and no camera (hence the paucity of photos today). No car either. We ate home grown vegetables when possible. Heating was from an open fire, mainly burning other people’s timber building waste. We can never walk past a skip to this day. We simply cannot resist looking in for something that might be useful, or a source of warmth. We get this from our father.

In fact, it might be said that Dad lived by two rules – Rule Number One: never throw away anything that might one day prove to be useful; and Rule Number Two: be constantly alert to the opportunities created by other people’s failure to adhere to Rule Number One.

[Chris] During this time, Dad decided that he was gay. This cannot have been easy for him or, especially, for Mum. They decided to stick together, not just for our sakes (although this was certainly a major factor) but also because they had become best friends and, both being a little odd, although in different ways, found that they really needed each other to manage in the world, having what you might these days call complimentary skillsets.

Shortly, Mum is going to talk more about what Dad’s sexuality meant for their lives and how Dad became an advocate for the gay community.

[John] Also at this time, Dad took a demotion to work in the field, helping indigenous kids more directly than was possible from an office in Sydney. He was offered a posting in either Dubbo, Moree or Orange. He and Mum chose Dubbo, partly because of his jackerooing experience in that part of NSW, and our family moved to Dubbo in 1976.

Anyway, Dad (now aged 48) was back in Wiradjuri country where he had jackerooed as a young man, and not that far from where his mother had been born. His first office was in Oliver House – a very notable building in Dubbo (not so much because it was unique in being named after a trade unionist, but because it was the only building in town with a lift).

We rented in two houses in different parts of town. Then, in 1979, Dad bought a house at 287 Fitzroy Street in South Dubbo [Slide 10] with the result that Chris and I attended different schools, and each forged our own identity, rather than being known as the Sergeant brothers. This was a deliberate policy. This house was near the top of the only real hill in the town itself. The house was big enough for both our maternal and paternal grandmothers to come and live with us in their last years, which they did.

[Beth] A big drawback for David in Dubbo was the scarcity of gay company. Despite a few notable exceptions, gay men in country areas tended not to be “out” and were thus hard to identify. Like David, they suffered from isolation and, potentially, from prejudice. David dealt with this by setting up a network of country gays (or city gays with a love of the country).

Looking back, the Country Network, as it became known, had rather amusing birth pains. Country newspaper advertising people assumed that an ad for friendship of one’s own sex is sure to be a practical joke against the person named, and only ‘The Land’ – the farmers’ newspaper - believed him.

As it happened, the first enquiries arrived in person when David was not home. Two men knocked at the door. I expected David back soon (no mobile phones of course in the 1980s). Somehow, I never thought to ask, “Have you come about the newspaper ad?” I just asked them to come in. They no doubt assumed David was acting behind my back (as if he would!) In fact, a fellow student at David’s wool classing course had asked for a lift to her country home, inviting him in for a cuppa. So, the very first two Country Network visitors sat on and on and on, making polite conversation and waiting very awkwardly until David finally showed up.

From this small, awkward beginning, the Country Network was born and gradually grew to its present state. John, Chris and I all helped in the early days, folding newsletters and addressing envelopes. Now, the Country Network is an amazing web-based organisation and everything is electronic … but it still requires dedicated people to make everything happen and we are glad that some Country Network members are here with us today.

However, David did not just found the Country Network. His interest in the environment also led him, with Mum and some other Dubbo people, to found the Dubbo Field Naturalists Society, which organised visits to interesting well-preserved places in the bush around Dubbo and campaigned for their protection and for the recognition of aboriginal custodianship of these special places.

[Chris] Being gay hadn’t really changed Dad. He was never the flamboyant type. Old habits of economising die hard. It was still seen as wasteful to pay for electricity, oil or gas for heating, especially when builders all over town kept throwing timber offcuts into rubbish skips. Better still, under Dad’s patient direction, we boys could keep warm without even burning the wood … by chopping and sawing whatever he brought home into suitable lengths.

At Fitzroy Street, there was a very big front garden, with a climbable cedar of Lebanon brought back home as a seed by a previous owner after WWI. Here is a family photo taken by me in the front yard [Slide 11].

The house had not one but two back yards, the rearmost containing the remnants of an old citrus orchard and a workable chook run. The chooks were never particularly prolific producers, but the fruit trees certainly were, and we devoured a bucketload of navel oranges every day or so in winter. Dad loved caring for the garden … and getting us to do so. So, it is fitting that we will sprinkle some of his ashes later this afternoon in John & Jenny’s garden here in Glebe.

[John] Of course, Dad had been a jackeroo, he had studied agriculture, he had even taught agriculture, so a mere garden, no matter how large, would never satisfy him in the way that a farm could. He and Mum ended up buying a 72 acre block at Toongi, about 20km south of Dubbo, not far, as it happened, from the Springs, where he had first got a taste for life on the land. Dad chose a largely northeast facing piece of basalt country, guaranteed to be productive. About half of it was ploughland, growing winter wheat, and the rest seemed particularly well-suited to producing thistles and burrs of various types, along with some fine stands of cypress pines.

This block of land was a boon for Chris and me. We have never been so fit as when we were employed as child labourers there working under Dad’s supervision. We spent long hot days, improving the property by using a crowbar to lever out rocks, pruning the lower branches of cypress trees, digging contour banks by hand, chipping away at thistles with a hoe or pumping water with a hand pump to keep a few struggling fruit trees from withering in the unrelenting sun. All done to Dad’s perfectionist standards. Mechanised farming was for sissies.

Cypress pine is a beautiful but very slow-growing timber, ideal for flooring. But it is only useful if the grain of the wood is true and runs parallel with the floorboard. So, Dad’s mission was to use child labour which, after all, is very cheap, to keep the straight cypress saplings alive and remove any bent ones. This seemed ironic, given that Dad was decidedly bent himself. Anyway, this and other work would be rewarded not with an ice-cream or a milkshake on the way home but with the promise of future riches when the trees were mature … in another 100 years.

[Chris] I still remember, on those drives to and from the block, stopping numerous times in the car to collect old hessian fertiliser sacks, and aluminium cans. Dad never wanted to waste a stop and so we would be encouraged to scour the surrounding area for other ‘treasures’ or perhaps for a suitable piece of firewood or two. Once, the car struck and killed a hare, so guess what we had for dinner? Several dinners in fact.

Much later, when we boys had both moved away and the block had become too much for him and Mum to care for, and they were preparing to move to Sydney, Dad decided to give it away, quite literally, to the bloke who mowed their lawns in town, and who, like Dad had, dreamed of one day owning a farm. So, he gave the farm away and those lovely straight cypresses pines now belong to some else.

On one of the few occasions that Mum went away, she left a beef stew to last a few days…well waste not want not, thought Dad, and that stew continued to get eaten each evening and then augmented with home-grown parsnips to pad it out and make it last another day. By the end of the week, it was more akin to parsnip soup than anything anybody would recognise as stew. It took a long time before we boys could face a parsnip again.

Despite his scientific background, he was also very much of a view that the body heals itself, given the right diet and rest. For example, on a winter Sunday morning, I was kicking a football around with one of our neighbours in the school behind our house at Fitzroy Street. I slipped on the dewy grass and was in significant pain with what even a 14 year old boy could tell was a broken arm. Upon presentation to Dad, his scientific approach conflicted with his no fuss approach and he decided that we would leave it for a while to see if it got better. I realised later that he was waiting for mum to get home with the car so that I could be taken to hospital – rather than go to the fuss of a taxi or heaven forbid an ambulance!

[John] By this stage, we were able to get a TV. There were then two channels available. We watched only one of them. We delighted in gathering round the tiny set in the only warm room in the house to watch I Claudius, Rumpole of the Bailey, The Onedin Line, Dave Allen and the Two Ronnies. We also tried to cheer on Eddie Charlton, the only Australian snooker player on Pot Black, although it was a bit hard to follow the action … until we became the last people in the developed world to upgrade to colour television.

Despite never quite keeping up with the Joneses, or even trying to do so, we always felt loved and we never felt judged, although feelings were not much spoken of. Whether we boys did well or badly, there was neither praise nor criticism. We never really knew how our parents felt, which meant that we were never under any pressure to do well at school or at sport. Again, this was a deliberate and scientifically-based policy designed to engender intrinsic motivation.

Generally, Dad was happy for us to make our own way in the world, so much so that we each received a suitcase on our 18th birthday. Unlike Chris, I was lucky enough to be given a brand new one.

As was expected, we boys moved to Sydney to study and, in due course, got married to Sydney girls (if Camden can be considered as such). One of us married slightly more often than the other and we are grateful that Astrid, Melissa and Jenny are all here with us today. Here are some photo’s of Dad at my weddings. [Slide 12, Slide 13]

[Chris] Going through my own wedding photos in preparation for today, I realised that there were none of Dad. Melissa then reminded me that he couldn’t make it (we did only provide 6 months’ notice after all), and she reminded me of a line my brother gave at our wedding, which I’m sure confused some people who didn’t know the backstory of my adoption and recent connection with Jeannette ‘I stand before you with two mothers and no father’…well that is certainly never more true than today.

As it happened, Dad at that time spent almost half of each year in Hanoi, and he saw it as extravagant and impractical to fly back to Sydney for our wedding. In Hanoi, he was teaching technical English to science students, so that they could read and, it was hoped, eventually write publications in learned journals, which were all in English. Like his Colombo Plan students, some of these people have also become family friends and many have left Vietnam to pursue careers abroad, including here in Australia. Here is a photo from one of his first Vietnam trips [Slide 14]. And here is a picture taken on one of his last trips [Slide 15].

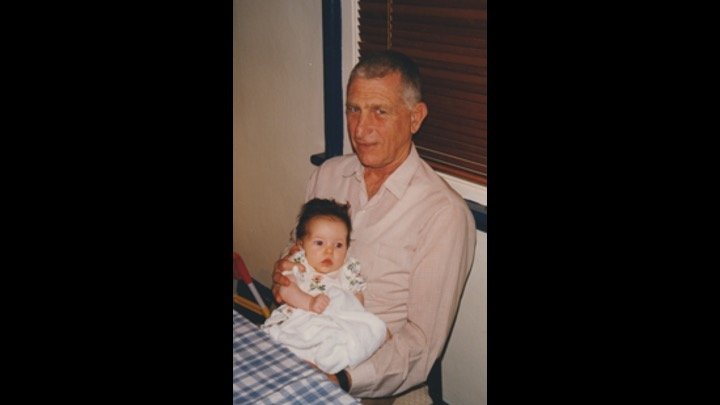

In 1995 Dad became a grandfather, with the birth of Genevieve [Slide 16, Slide 17]. Over the next 21 years, there followed Louisa, Grace, Lachlan, Peter and finally Arthur. None of the grandkids lived in Dubbo, of course. And a visit to Sydney is quite a big undertaking for country folk. As the grandchildren grew older and more numerous over the years, Dad became more and more overwhelmed by the size and the pace of Sydney. Fitzroy Street was too big for them too, so Mum and Dad moved to a smaller house in Gipps Street, Dubbo in 1997. [Slide 18] Here are Melissa and Grace visiting Gipps Street.

Dad was always an activist, not just trying to help those in need but thinking about how society and the world could be changed to better provide for the less privileged and to eliminate the causes of disadvantage, conflict and poverty. While he disliked Gough Whitlam as a person, he was supportive of the Whitlam Government’s social reforms and outraged at the dismissal. And, while also disliking Malcolm Fraser, he applauded the generosity of spirit shown by the Fraser government in accepting so many Vietnamese refugees. When George Bush and his local self-described Deputy Sheriff John Howard embarked on the so-called “War on Terror” - illegally invading first Afghanistan and then Iraq – Dad handwrote on the outside of every envelope he posted the words “War IS Terror”. He knew this to be true. He was, unsurprisingly, a supporter of Australians for Native Title and Reconciliation. While he could always surprise you with his views, we have no doubt that he would have voted “Yes” in the upcoming referendum.

In 2011, David was asked to come to Sydney to attend the Aids Council of NSW’s annual awards night. Mum stayed in Dubbo so I went as Dad’s partner. Those present assumed I was his young lover and they were correct in one sense. I did love him and was very proud of what he had achieved for gay people facing the many challenges of living in rural and regional Australia.

As I recall, the event was jointly hosted by David Marr (Patrick White’s biographer) and the incomparable Marcia Hines. I was a bit starstruck. Dad, on the other hand, being raised from a young age to ignore popular music, had no idea whatever who Marcia Hines was. Indeed, he suspected that she might actually be a drag act, and was trying to work out what vulgar pun was embedded in the sound of her name. All sorts of awards were handed out. At the end of the evening, to his surprise and embarrassment, Dad was presented with the highest honour and made a hero of the gay community. This is a bit like being a hero of the old Soviet Union. Here is Dad with the bouquet presented to him, with a kiss, by Marcia Hines. [Slide 19] He had not prepared a speech for the occasion. In fact, it was abundantly clear that he had never even used a microphone before!

Dubbo didn’t just have two TV stations. It also had two newspapers. His award was reported in one of them, with his permission and cooperation, and that effectively “outed” Dad in the local community. Here is the front page. [Slide 20]. Not wishing to be outdone, the other paper carried the same story, a year later [Slide 21].

[Chris] After almost 20 years in Gipps Street, Mum and Dad downsized again, moving to Lombard Street in Glebe in 2016. “I just want to make it clear that I have come to Sydney to receive care, not to provide it,” said Dad. Again, this proved to be correct. Funnily enough, although they had downsized twice by this stage, they still had every single item that Dad had ever thought might one day prove useful!

[John] Now that they lived in Glebe, it was good to have them close to Jenny and me, although by this time Chris and Melissa were a long way away, in London. Here is Dad on a visit to our home in Glebe, with Peter, Louisa and Genevieve. [Slide 22]. He had by this time given up his Vietnam trips. They were too much for him. A visit to London to see Chris and Melissa and their children was therefore out of the question.

[Chris] In 2017, Dad was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, although the warning signs had been there for at least two or three years. Perhaps his Alzheimer’s was hereditary. Perhaps it was environmental; the result of at least three serous loss of consciousness injuries. I certainly hope it was the latter, for the sake of his descendants.

Being at the end of a phone line is quite difficult in these situations (for everyone) and we found an opportunity for the Sergeants to kill more than two birds with one stone in 2019, when I was able to fly out when changing jobs to meet Mum, Dad and John in Adelaide and on to Kangaroo Island where John was doing a lot of work at the time. [Slide 23]. It was the first time we had been exclusively together on a holiday in a long time – probably since the early ‘80s. While it was obvious that Dad was going downhill, I also believe he got a lot out of the trip as a family, and it will always have a special place in my memories – especially with what happened soon after, with both the devastating KI fires, and then the enforced lockdown and being basically barred from coming back to Australia. It was the last time I saw him for over three years.

As terrible as the disease was, it did perhaps open his mind to more sharing … in 2020 I volunteered to be on the covid vaccine trial program in London with Astra Zeneca. Talking through it with Dad over the phone prompted him to recall a story of his work in the CSIRO in the late 1950s that hadn’t spoken of since that time – not even to Mum.

[John] Following his diagnosis, Dad continued to be cared for at home by Beth for four years. He was painfully aware that his mental powers were ebbing away. He could become angry, paranoid and obstinate at times; at other times he was happy and grateful to place his trust in others.

COVID made respite care difficult and delayed the process of getting him into care. It was not until 2021 that he could be placed into one of the dementia cottages at Uniting Care’s Marion facility at Leichhardt. The staff there do an amazing job. He enjoyed being visited and was at times quite proprietorial about his new home, but otherwise seemed deeply unhappy, as though the one thing that he retained was a sense of how much had been taken from him.

His death was peaceful and he was lucid enough to say goodbye to one of the staff in a full sentence, having been unable to express himself coherently for over a year. He said “I’m OK, thank you” when Maria, one of the staff, knowing that his end was near, said a last goodbye before leaving for the day. Dad died early that evening [Slide 24].

He died with a dignity that typified him, even when all dignity had seemingly been taken from him.

So, a remarkable life; a truthful and upright man. A life of care for those in need, in Australia and abroad, for the gay community, for civil liberties, for the environment and for his family. In short, a life well worth celebrating. We should give thanks that our lives, and so many others’, were touched and shaped by his.

You can find more articles like this one by clicking the tag below, or to find more articles by this member, click on their profile image.